|

United Nations

reform:

Where is

Kofi Annan's "fork in the road"?

Over the horizon!

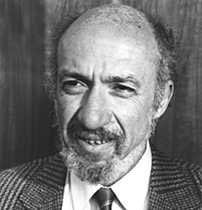

By

Richard

Falk

Comments directly to

rfalk@Princeton.edu

December 8, 2006

I. Metaphor and the Politics of Despair

In addressing the General Assembly back in

2003 on the urgent need for UN reform, the Secretary-General of the United

Nations, Kofi Annan, resorted to a frequently quoted metaphorical trope:

“Excellencies, we have come to a fork in the road. This may be a

moment no less decisive than 1945 itself, when the United Nations was

founded.”

He explains the rhetoric by saying “[n]ow we must decide whether

it is possible to continue on the basis agreed upon or whether radical

changes are needed.” And further, Annan notes that he had earlier

“drew attention to the urgent need for the [Security] Council to

regain the confidence of States, and of world public opinion—both

by demonstrating its ability to deal effectively with the most difficult

issues, and by becoming more broadly representative of the international

community as a whole, as well as the geopolitical realities of today.”

[The Secretary General Address to the General Assembly, Sept. 23, 2003,

pp.1-5, at 3]

To build support for the needed radical changes, that is, to ensure that

the right road is chosen at the fork, Annan appointed two panels designed

to shape an agenda for the General Assembly’s reform summit scheduled

for the Fall of 2005, the 60th anniversary of the UN. Both appointed groups

operated according to a realist calculus that tried to take account of

what sorts of changes would be acceptable to a majority of the membership.

The less significant of the two was the Panel of Eminent Persons on UN-Civil

Society Relations, chaired by Fernando Henrique Cardoso, the former President

of Brasil. Its mandate was narrowly framed to encourage proposals that

would give civil society organizations somewhat better access and opportunities

for participation, but within the existing pattern of the UN System. The

127 (?) recommendations of the Panel were rather technical and managerial

in tone, and whether implemented or not, unlikely to alter the basic non-impact

of global civil society on important UN undertakings. [See Falk in GS

Yearbook; Cardoso Report]

The more important initiative was that High-level Panel on Threats, Challenges

and Change that issued a widely discussed report entitled “A more

secure world: Our shared responsibility.” [(New York: The United

Nations, 2004)] In the transmittal letter to the Secretary-General, prefacing

the report, the panel chair, Anand Panyarachun, observes that “[o]ur

mandate from you precluded any in-depth examination of individual conflicts

and we have respected your guidance. But the members of the Panel believe

it would be remiss of them if they failed to point out that no amount

of systemic changes to the way the United Nations handles both old and

new threats to peace and security will enable it to discharge effectively

its role under the Charter if efforts are not redoubled to resolve a number

of long-standing disputes which continue to fester and to feed the new

threats we now face. Foremost among these are the issues of Palestine,

Kashmir and the Korean Peninsula.” [p.xi]

This passages thinly disguises the double bind embedded in the mandate

given to the Panel: who address threats to peace in the current global

setting, but without treading on toes by discussing specific conflicts.

As any inquirer knows, the only way to grasp the general is by attentiveness

to the particular, and this is precisely what is precluded. Hidden here

in the bureaucratic jargon of the UN is the decisive obstacle to the sort

of UN reform that is, indeed, urgently needed if the Organization to realize

the goals of its most ardent supporters and to move in the directions

encouraged by the UN Charter, especially its visionary Preamble. It is

not possible, even in the spirit of advocacy, to take on the most serious

existing breaches of peace and security, or even the most serious proximate

threats.

Despite these restrictions, the Panel does face the new realities of the

twenty-first century in ways worthy of discussion, especially on issues

of peace and security. Three aspects of its approach are illustrative

of its image of reform. Each is situated within a realist calculus of

reformist feasibility, but still lacks serious prospects for implementation

because of a failure to take account of the minefield that makes taking

the road to reform treacherous. The High-level Panel suggests 1) broadening

the idea of security by taking account of the rising support for the concept

of ‘human security,’ and treating issues of disease, poverty,

environmental degradation, and transnational organized crime as falling

within the ambit of security.[21-55] 2) that the new threats to world

order associated either with transnational terrorism or crimes against

humanity/genocide can be addressed within the existing Charter framework

if the right of self-defense as set forth in Article 51 is “properly

understood and applied.” [p.3]

The reformist element here is to insist that

such an extended view of the use of force in self-defense, including its

justifications for preemption and intervention in internal affairs, requires

prior UN Security Council authorization. 3) Following the recommendation

of the Canadian International Commission, an endorsement of “the

emerging norm that there is a collective international responsibility

to protect, exercisable by the Security Council authorizing military intervention

as a last resort, in the event of genocide or other large-scale killing,

ethnic cleansing or serious violation of international humanitarian law

which sovereign Governments have proved powerless or unwilling to prevent.”

[66]

These proposals walk a series of tightropes.

To begin with, the tightrope that allows

the broadening of the idea of security to include threats to human wellbeing

while being respectful of the overarching concern with threats to use

force against a state mounted by state and non-state actors. Overall,

acknowledging geopolitical pressures to engage in preemptive responses

based on the rhetoric of the post-9/11 Bush approach to national security,

while being sensitive to the wider allegations of unilateralism that have

been directed at American foreign policy, especially in the wake of the

Iraq War. They also walk a third tightrope that is responsive to the importance

of the human rights movement that is a high priority for global civil

society while being overtly deferential to the traditional prerogatives

of sovereign states, expressed both by the norm of nonintervention and

by a recognition that international action is only legitimate if the state

fails to address an ongoing humanitarian catastrophe. Each of these moves

seems entirely consistent with the Westphalian concept of world order

based on the interplay of sovereign states, as modified by the development

of international law, and as adapted to a changing global setting.

And yet this agenda is subject to lines of

decisive criticism: the Panel’s proposals go too far given the geopolitical

climate; the proposals are far too modest given the claimed intention

of the reformers to live up to Charter expectations as to collective security

or to safeguard the world against the menace of unilateralism.

Why too far? The United States, in particular, has made it abundantly

clear that it will determine on its own whether to rely on force to address

international conflicts, and without regard to Charter constraints given

its insistence that threats must be dealt with by preventive and preemptive

modes of warfare. As long as the veto is available to the five permanent

members of the Security Council, any effort to impose international restraints

on their behavior depends on their voluntary compliance. And further,

it remains the case that the responsibility to protect is an empty norm

without either endowing the UN with independent capabilities or generating

a political will on the part of leading states to provide needed levels

of support either in advance or in response to humanitarian emergencies.

There is no evidence that such conditions will be met. The feeble response

to the massive genocidal developments in Darfur in the face of the complicity

of the Sudanese government is ample evidence that the political will is

absent to support the norm associated with a responsibility to prevent.

The reformist road advocated by the Panel seems blocked for the foreseeable

future by geopolitical resistance that should have entirely predictable.

Why not far enough? The Panel’s proposals

purport to change policy without altering the constitutional status of

the permanent members within the United Nations and without providing

capabilities and institutional procedures to make their recommendations

assume a meaningful political character. To be more specific, the only

way that the Security Council could be meaningfully empowered to implement

the suggested supervision over extended claims of self-defense is to deny

the availability of the veto to permanent members, but the issue is left

untouched. Similarly, the only way that an interventionary mission to

discharge the responsibility to protect could become credible would be

through the establishment of a UN Emergency Peace Force that was trained

in advance and independently financed and recruited. Again, such an implementing

procedure is not even discussed.

Finally, to make the enlargement of the security

agenda more than words requires some sort of institutional recognition

that these new issues are deserving of inclusion on the agenda of the

Security Council to the same degree as war/peace concerns. Because such

a recognition would highlight the disparity of economic conditions in

the world economy, creating pressures for a more equitable distribution

of the benefits of economic globalization that arises from neoliberal

policies, there is no present prospect that the call for a comprehensive

approach to security will yield behavioral results, except of a kind that

would have been produced in any event, for instance, inter-governmental

cooperation to control transnational organized crime.

For these reasons, the only responsible conclusion

is that the report of the High-level Panel failed from either a realist

perspective of politics as the art of the possible or an idealist perspective

as politics as the quest for the necessary and desirable. Its main proposals,

although carefully formulated and sensitive to the global setting, only

reinforced the mood of despair surrounding issues of global reform.

In this sense, perhaps imprudently, the Panel

accepted an assignment that seems an example of a ‘mission impossible.’

Returning to the fork in the road, there

is no fork, only the old geopolitical pathway dominated by geopolitics

and statism. Kofi Annan’s use of this metaphor is an expression

of false consciousness, especially as related to its animating subject-matter,

which was the combination of American unilateralism with respect to war

making and a general atmosphere of inaction in response to humanitarian

crises. Prior to inserting the metaphor, the Secretary-General calls attention

to the dangerous precedent posed by “this argument” that “States

are not obliged to wait until there is agreement in the Security Council.

Instead, they reserve the right to act unilaterally, or in ad hoc coalitions.”

He adds that “[t]his logic represents a fundamental challenge to

the principles on which, however, imperfectly, world peace and stability

have rested for the last fifty-eight years.”

Annan admits that ‘it is not enough

to denounce unilateralism, unless we also face up squarely to the concerns

that make some States feel uniquely vulnerable, since it is those concerns

that drive them to take unilateral action.”[p.3]

It is here that there is a failure of comprehension,

and an insight into how such a mission impossible is launched. Of course,

the whole discourse is beset by the taboo associated with mentioning particulars,

that is, which state resorted to war for what apparent purpose. It is

obvious from the setting that Annan was talking about the American invasion

of Iraq, but to suggest that this invasion was a response to an American

post-9/11 sense of ‘vulnerability’ is to ignore the overwhelming

evidence that the Iraq War was initiated for reasons of grand strategy,

and the anti-terrorist claims of an imminent threat were trumped up and

quite irrelevant to the policy.

The point here is suggest that if the true

pressures on the UN framework are not properly analyzed there is no way

to fashion a relevant response. The High-level Panel was completely responsive

to the Secretary-General’s mandate, providing momentary cosmetic

relief, but also deflecting a more accurate understanding of the challenge

being mounted against the role of the United Nations Charter by prevailing

patterns of geopolitical behavior.

Decades before the Iraq War, the issue of

Charter obsolescence had been widely discussed. [Perhaps, most notably,

by Thomas Franck in “Who Killed Article 2(4)? Or: Changing Norms

Governing the Use of Force by States,” 64 AJIL 809(1970).] Many

international law specialists have pointed to the practice of states that

cannot be reconciled with Charter constraints on recourse to aggressive

war as an instrument of policy. [See Weisbrod; Arendt & Beck] More

recently, Michael Glennon has been tireless in his critique of what he

regards as ‘legalism,’ even Platonism, contending that it

interferes with a realization that the UN Charter system for restraining

states was never truly implemented as a collective security mechanism,

has not been respected by important states, and lacks constraining weight

and authority. [Michael J. Glennon, “Platonism, Adaptivism, and

Illusion in UN Reform,” Chicago Journal of International Law 6(No.

2):613-640(2006)]

Glennon goes further, lending a provisional

vote of confidence to what he calls “ad hoc coalitions of the willing”

that “provide an effective substitute” “on specific

occasions” for the Security Council, referring to the Kosovo War

launched in 1999 under NATO auspices as his justifying example. He argues

that it was correct to disregard the absence of Security Council authorization

for a non-defensive use of force, and that the NATO authorization, although

not based on international law, was sufficient.[639; see the Report of

the Independent International Commission on Kosovo (Oxford, UK: Oxford

University Press, 2000) for a different approach, pp. 000]

The Kosovo example is misleading as the coalition

of the willing was responding to a credible humanitarian emergency of

limited scope, and not embarking on a geopolitical adventure that rested

neither on moral or political imperatives. To move in Glennon’s

direction is to endorse the geopolitical management of world politics

at a historical moment in which the dominant state enjoys diminishing

respect as a hegemonic actor and confronts deepening resentment arising

from its policies. In this regard to shore up the advocacy of global policy

fashioned by coalitions of the willing by historical reference to the

relative success of the Concert of Europe in keeping the peace in Europe

during the nineteenth century.

At the same time, the prohibition in the

Charter is a key foundation for challenging the legality and legitimacy

of state action by either moderate states or the forces of global civil

society. To the extent that a post-Westphalian form of democratic and

humane global governance is struggling to become a political project it

depends for clarification of its undertaking on the norms associated with

the UN Charter and the Nuremberg tradition of imposing criminal accountability

on leaders of states. [For fuller exposition see Falk, The Declining World

Order (New York: Routledge, 2004); also Falk, Gendzier, and Lifton, eds.,

Crimes of War Iraq (New York: Nation Books, 2006)]

To summarize, the metaphor as used by the

Secretary General to encourage a process of UN reform was influential

in guiding those entrusted with shaping an agenda of proposals and recommendations.

But it was deeply misleading in the sense that it acted as if there existed

an alternative to geopolitics that could be effectively developed by inter-governmental

consensus.

The Secretary-General could have

resigned

Far more appropriate as a metaphorical gesture

of credible substance would have been the resignation of the Secretary-General

precisely because there was no fork in that road! “Without a fork

in the road I cannot continue to serve this world Organization in good

faith!” And elaborating by saying that “due to the recent

circumstances highlighted by the Iraq War, the prevailing path has become

untenable, a betrayal of the core principle of the Charter prohibiting

aggressive war.”

If Kofi Annan, surely a decent person and

dedicated international civil servant had so used the metaphorical moment,

two positive results could be anticipated: first, a wider appreciation

that needed UN reforms of even minimal scope were presently unattainable;

and secondly, a pointed recognition that the United Nations could not

function as intended due to obstructionist tactics of the main geopolitical

actor, the United States.

Such a posture would have given Annan a voice

of his own as well as an audience in civil society that might well have

regarded the occasion of this resignation as an opportune moment to launch

a struggle for the soul of the United Nations.

Whether the path presently being cleared by the more progressive forces

in global civil society is more than a utopian gesture will not be known

for decades, but it is the only path that makes the abolition of aggressive

war, at least potentially, ‘a mission possible.’ Aligning

with this struggle is the only emancipatory option available to those

seeking a humane form of global governance. [See Alain Badiou, Meta-Politics

(London, UK: Verso, 2005)]

The metaphor ‘a fork in the road’

can thus be inverted so as to clarify the historical circumstance, acknowledging

both the absence of choice, from within a Westphalian framing of UN reform,

and the possibility of choice achieved by way of a rupture with standardized

organizational expectations associated with delivering the case for reform

by relying on a rhetoric of urgency that is immediately contradicted by

patterns of performance that submit to the dual disciplines of bureaucratic

inertia and geopolitical discipline.

That the outcome of this dynamic, as evident

in the two reports, whose recommendations were further diluted in the

Secretary-General’s own later report, In Larger Freedom, has been

pathetic from a reformist perspective should not come as a surprise. [In

Larger Freedom: Towards Development, Security and Human Rights for All,

Report of the Secretary General, (New York: United Nations, 2005).] Nor

should the bureaucratic cover up by way of a hollow celebration that pretends

that the meager and marginal steps taken at the World Summit in 2005 responded

adequately, even impressively, to the original urgent call. [“Implementation

of decisions from the 2005 World Summit Outcome for action by the Secretary-General,”

Report of the Secretary-General, 25 Oct 2005, A/60/430.]

What becomes manifest in the course

of this cycle of delusion, is a circular and mutually complicit demonstration

of the exact opposite from what is officially explicated: namely, the

impossibility of UN reform. Acknowledging this impossibility is the only

way to overcome it. To the extent that Kofi Annan, knowingly or unknowingly,

both articulates the urgency of reform and the cover up of its failure,

he is playing the villain’s role in this geopolitical theater of

the absurd.

We are left with Glennon’s overt dismissal

of the UN, and avowal of the primacy of geopolitics, as a more trustworthy

rendering of the global setting in the early twenty-first century than

is the false advertising associated with official UN efforts. [Glennon,

note 00]

In the end, better a counsel of despair than an over-dosage of anti-depressants.

Better only because it prompts resistance that is rooted in the realities

of what exists rather than perpetuating a pattern of escapist delusion.

II. Horizons and Metaphors of Hope

From its inception the United Nations represented

an uneasy Faustian bargain between an idealist search for peace through

law and the realist quest for stability through power. On the idealist

side, is the unconditional prohibition of force except in instances of

self-defense strictly defined to require a prior armed attack, reinforced

by collective security mechanisms that were intended to protect states

that were victims of aggression.

On the realist side, is the grant of veto

power to the five permanent members of the Security Council, further accentuated

by the short-term dependence of the Organization on financial contributions

from member states, especially the leading ones, and by an overall relationship

to the Charter that is premised on voluntary adherence, respectful of

sovereign rights.

Such normative incoherence is bound to generate

disappointment, with idealists expecting too much and realists not expecting

anything at all beyond discussion. The operative impact of this Faustian

bargain has been evident in relation to the Iraq War, with idealists delighted

that the Security Council refused to authorize the invasion in 2003, while

realists bemoaned the irrelevance of the Organization. Subsequent to the

invasion, despite its flagrant violation of the most basis principle of

the Charter, the UN acquiesced in the outcome, lent its support to normalizing

the illegal occupation of the country, and refrained from criticizing

the invasion and occupation.

Through the years, off camera, the UN achieved

many positive results, often beyond most reasonable expectations, and

far beyond what its predecessor, the League of Nations achieved, especially

in such areas as human rights, environmental consciousness, health, care

of children, education, and even in relation to peace and security whenever

geopolitical actors happened to be united in approach. A testimony to

this net contribution to human wellbeing is that no state has withdrawn

from membership in the United Nations over the entire course of its history.

[The one partial exception is Indonesia that withdrew for a year in 1965

to form a counter-organization of ‘new states,’ but returned

after discovering an absence of receptivity to its efforts.]

Given this circumstance, it is not surprising

that the UN reform process is so clogged. There are three sources of resistance

to substantial reform, each quite formidable:

• the amendment process is constitutionally

difficult, and is subject to the veto;

• the entrenched advantages of

some states, and the diverse priorities of different regions, makes

it difficult to achieve a consensus on specific steps (unless innocuous);

• the leading states, especially

the United States, are unwilling to cede control over vital dimension

of global policy or to allow initiatives within the Organization

that express criticism of its global role or specific policies.

With these considerations in mind it is hardly surprising that the

UN has not been able to solve the most pressing demands for the

kind of reform that would provide it with enhanced twenty-first

century legitimacy:

• changing the membership of

the Security Council to take account of shifts in influence since

1945;

• adapting the concept of self-defense

to the current realities of international conflict without giving

states the authority to wage discretionary wars;

• acknowledging the impact of

the global human rights movement to the extent of creating capabilities

and willingness to intervene in internal affairs in reaction to

the threat or actuality of genocide or crimes against humanity;

• taking advantage of the end

of the Cold War to embark upon a path of negotiated nuclear disarmament,

to establish an emergency peace force to deal with humanitarian

emergencies and natural disasters, to establish a global tax that

will provide an independent revenue base, and to create a global

parliament in recognition of the rise of civil society.

It is with this understanding of an agenda

for UN reform that makes it suggestive to rely on the metaphor of ‘horizons’

as clarifying, acknowledging formidable difficulties without being demoralizing.

[Falk, TWQ article on Westphalian pessimists and optimists] A basic distinction

needs to be drawn between horizons of feasibility and horizons of desire.

Horizons of feasibility refer to those adaptations

needed to make the Organization effective and legitimate within its existing

framework, that is, with an acceptance of the normative incoherence associated

with the tension between the Charter as law and geopolitics as practice.

In contrast, horizons of desire, are based

on overcoming this incoherence by minimizing the impact of geopolitics.

This presupposes solving the challenge of global governance by transforming

the United Nations in manner that achieves primacy for the Charter’s

goals and principles.

Such a possibility, currently an impossibility,

would depend on a much more widely shared perception as to the dysfunctionality

of war as an instrument useful for resolving conflict and creating security.

A transformed UN in these directions would provide an institutional foundation

for moral globalization, that is, for the realization of human rights

comprehensively conceived to include economic, social, and cultural rights,

as reinforced by a regime of global law that treated equals equally and

was not beset by claims of exception and by an ethos of nonviolence.

As suggested in the discussion of ‘the

fork in the road’ it would be futile to consider such a transformative

horizoning as relevant to the present or likely discourse on UN reform

within the conventional arenas of statecraft, including the United Nations

itself. Even the horizons of feasibility, other than moves to achieve

managerial efficiencies and marginal adaptations, seem unpromising, although

it is possible to imagine shifts in the political climate that could lead

to adjustments in the makeup of the UN Security Council to make it more

representative or a successful initiative to establish some kind of emergency

force that would give the UN more credibility with respect to interventions

for humanitarian purposes.

If we take account of the recent past, the

most successful reform developments have resulted from ‘coalitions

of the dedicated’ (compare the geopolitical inversion - coalitions

of the willing, as in Kosovo, Iraq) that have been composed of likeminded

governments and a movement of civil society actors. Both the anti-personnel

landmines treaty and the International Criminal Court (ICC) came about

despite the geopolitical resistance led by the United States, and illustrated

the potential reformist capacity of a ‘new internationalism’

that is neither a project of statist nor of global civil society, but

a collaboration that draws strength from this hybrid agency.

Of course, it would be a mistake to attribute

transformative potential to this new internationalism as it is unclear

whether it can move beyond formal successes. The anti-personnel landmines

treaty, while symbolically important, addressed a question of only trivial

relevance to geopolitical goals and the ICC has yet to demonstrate that

it can be a robust contribution to the effort to make individuals who

act for states criminally accountable.

The argument being made is based on an acknowledgement

of the need for UN reform, while trying to rid the quest of false expectations

and empty rhetoric. The metaphor of horizons establishes goals without

regard to political obstacles, and then distinguishes between those goals

that might be achieved by existing mechanisms of influence, horizons of

feasibility, and those goals whose implementation is necessary (and desirable)

but for which there cannot be currently envisioned a successful scenario.

These latter goals of a transformative depth

are thus situated over the horizon. Their pursuit can be understood either

as a new political imaginary for world order in the manner depicted by

Charles Taylor in Modern Social Imaginaries or as a waiting game for the

inevitable breakdown of the Westphalian world order that might convert

a transformation of the United Nations into a political project. [Taylor,

Modern Social Imaginaries (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004)]

In this regard, it might be recalled that

the League of Nations became a plausible, if flawed, project only after

the devastation of World War I, and the United Nations was only conceivable

in the wake of World War II. Each project was intended to ‘fix’

fundamental deficiencies of world order by shifting the horizons of world

order politics, and each effort moved beyond what seem previously attainable,

yet each fell far short of horizons of desire and longer term necessity.

III. A Concluding Note

Returning to the metaphorical motif,

this essay contends that there is no fork in either road, and that the

metaphor of choice is profoundly misleading and distorting. Within the

United Nations System, as now constituted, there is no reform choice,

and no alternative to the persistence of a geopolitically dominated reality.

Outside the UN, the commitment to UN reform by civil society actors is

the only worthwhile path, although the realization of its vision cannot

even be imagined at this point, but again, there is no choice to be made.

Choosing the geopolitical road to the

future is to close one’s eyes to the near certainty of disaster.

The only road that promises a sustainable and benevolent future now appears

utopian, but given certain unforeseeable developments, could become politically

viable.

Given this assessment, it follows that the

fork in the road metaphor should be rejected. Instead, the reliance on

the metaphor of horizons can be substituted in a dual mode: horizons of

feasibility for reforms within existing structures, and horizons of desire

for transformation that require radically modified structures.

It is the further claim being made here

that both horizons are part of an encompassing social imaginary that can

be named as horizons of necessity.

The perspective is guided by ancient wisdom:

“at the started, they laughed; later on, they began to listen, and

a bit later, they cheered.”

Copyright

© TFF & the author 1997 till today. All rights reserved.

Tell a friend about this TFF

article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

Get

free TFF articles & updates

|