|

The Iraqi elections - democratic

breakthrough or U.S. victory?

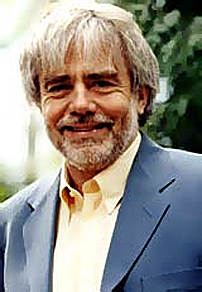

Per Gahrton, TFF Associate*

May 22, 2010

Editor's note: This article was written immediately after Gahrton's return from the elections, but its posting was inadvertently delayed. However, as the reader will understand it is still relevant and offers both on-the-spot insights and interpretations about these important elections.

When I together with the Danish ambassador and twenty American bodyguards, with helmet on my head and a bullet-proof vest, several ours delayed because of explosions and menacing incidents, finally reached a polling station in Baghdad on March 7, I almost did not have time to say hallo to the responsible functionaries before my voice was drowned by a major bang on the street outside. The body-guards ordered an immediate retreat to the Green Zone, the protected enclave of the occupiers, which used to be the centre of power of Saddam Hussein.

What struck me was that none of the dozens of Iraqis present, voters, functionaries, observers from NGOs and political parties, journalists and police officers, even raised their eyebrows. The voting continued totally unaffected by the explosion. Such was, according to my impressions and the reports of most observers, national as well as international, the situation all over the country.

When I a couple of hours later met with Faraj Haydari, Director of IHEC, the Independent High Electoral Commission, when he was voting in the VIP-polling station in Rashid Hotel inside the Green Zone, he discarded all reports pretending that the elections had been disturbed by violence. "Just some Molotov cocktails", he said. As a matter of fact, 38 fatal casualties on Election Day to most Iraqis was a rather low figure compared to the total chaos only few years earlier. Everybody I met assured me that the security has improved considerably, despite the recurrent reports of bloody incidents and killings.

Maybe the Iraqis have become so used to violence since the illegal US invasion of 2003 that they are blind to the blatant absurdity of the situation, or as one of my colleagues in the observation team from the Ottawa-based International Election Monitors Institute (IEMI) formulated it: “How is it possible that a small team of six international observers seven years after the ‘liberation’ cannot move around freely in Baghdad, but have to be accompanied by four car loads of body guards to be allowed to enter the Red Zone (i.e. everything outside the Green Zone)?”

Under such circumstances the contacts with Iraqis were of course distorted. Anyhow I don’t regret having accepted to observe the Iraqi elections of March 7 as “imbedded” with the occupier. That gave me insights that I could not have got as a normal journalist. To be the only European (together with a conservative British former MP) visiting US military bases, staying at the US Embassy – which is now being enlarged to become the biggest in the world - fly with US helicopters, be transported in US armored vehicles, all the time listening to US excuses, hopes and intentions about Iraq, is, unfortunately, just as important for the understanding of the situation of Iraq as contacts with the Iraqi population.

Several of the most severe critics of the US invasion, such as Patrick Cockburn in “The Occupation: War and resistance in Iraq”, maintain that the USA is implementing the old colonial control mechanism “divide and rule” in order to partition the country into three parts, Kurdistan in the north, the Sunni triangle in the center and Shiastan in the south, thereby destroying a potential independent Arab center of power in the middle of the oil belt of the world.

U.S. representatives in Baghdad claim that the opposite is true and maintain that it is the neighbours who wish to see a weak and divided Iraq. The USA, they claim, is interested in a strong central government in Baghdad. The explanation for that is simple; the USA wants to have Iraq as a “steady and long time partner”, as it was formulated by the US ambassador at a reception for international observers.

Obviously, once more Iraq is given the role of bulwark against radical and anti-American Islamism, just us before the first Gulf War of 1991. The difference is that the USA then used a tyrant, who was infamous for his ruthless cruelty both against his own people and his neighbours. This time the protecting barrier against al-Qaida and the ayatollahs of Tehran is planned to consist of a democratic Iraq, which will free the USA from the disgrace of being an illegal occupier and the bad reputation of making alliance with any undemocratic regime, only it is one of “ours”, like for example Saudi Arabia.

This is why the parliamentary elections of March 7 was so important for the USA, or as it was expressed by the Chair of the Joint Chief of Staffs, admiral Mike Mullen in the military newspaper Stars and Stripes the day before the elections: “The result of the elections on Sunday will show how well the USA is making here”. The same thought I heard repeatedly expressed by Americans during my stay in Baghdad as if the elections were some kind of referendum about the U.S. role in the country.

Nothing showed that the Iraqis understood it in the same way. Despite my “captivity” at the American “protected workshop”, the absurdity of which was summarized some years ago in the title of a book by the American journalist Rajiv Chandrasekaran, “Imperial life in the Emerald City – inside Baghdad’s Green Zone”, I managed to get sufficiently close contacts with Iraqi reality, by personal contacts and Iraqi mass media, to be able to observe that the role of the USA was a non-issue during the campaign. This does not imply that the Iraqis didn’t bother. Even U.S. officials admitted that a vast majority of the Iraqis want the US military forces to leave their country.

The issue, though, is considered to be settled by the agreement between the USA and the Iraqi government that all U.S. troops should be withdrawn by the end of 2011. Since 2009 most of the U.S. military personnel has been withdrawn from patrolling in Iraqi towns and villages and not even the pro-U.S. Kurds, the only part of the population which, with some reason, consider the Americans as “liberators”, have demanded any prolongation of the US military deployment.

Instead of quarrelling about the role of the USA, the politicians during the campaign concentrated on mundane issues of everyday life, such as the lack of electricity, water and other basic commodities. 60 per cent of all Iraqis don’t have access to a toilet! And this in a country that once, not without reason, was presented as an emerging Arab welfare society.

Even if the disastrous wars of Saddam and his internal terror is to blame for a considerable part of the pitiful socioeconomic situation of Iraq, it is a well-known fact that most Iraqis seven years after the US “liberation” are considerably worse off than during the last meagre years of the Baath rule.

The only clear conclusion the Iraqis could draw from the last seven years has been that neither U.S. occupation nor Shia secterianism is appropriate to cope with the basic problems of everyday life. The populist Shia agitator Muqtada Sadr, who, despite his reactionary opinions about women, has sometimes been hailed by Western critics of the U.S. occupation because he, unlike some other Shia leaders, has been a staunch opponent of the US presence, did not show up during the election campaign but preferred to continue his theological studies in Iran.

Most of the major parties and political alliances struggled to recruit both Sunni and Shia candidates for their lists. Several small parties entered the campaign with openly secular programs. Several female candidates appeared on posters and in TV unveiled. A female candidate from the Renewal party at a meeting with international observers speculated about a break-through for “woman power” in Iraqi politics, partly because of the quota rule that guarantees a minimum of 25 percent of the 325 seats to women, partly because the female part of the population is estimated to be well over fifty percent, among them three million widows.

A female candidate from another minor party, The Unity of Iraq, argued that the men have made fools of themselves, which will give the women a chance, just like in Ruanda. Maybe it was because of fear of a considerable “female swing” that I in the VIP polling station at Rashid Hotel, no less than twice in just five minutes could observe how elderly men in dark suits from some of the ministries of the neighbourhood were unable to let their wives vote in peace on their own, but repeatedly offered to “help”. The excuse given by the functionaries present for not intervening against such infractions of the rules was not credible. Were I really to believe that elderly upper-class women in Baghdad should be illiterate? More likely, they were suspected by their husbands of planning to vote for real change, away from the patriarchy, that has brought Iraq so much evil.

When the delayed results finally were published at the beginning of April they showed that the feeling among the international observers, that there had been a “secular swing”, came true. The secular al-Iraqiyya list, under the leadership of former Prime Minister Iyad Allawi, got the highest number of seats, 91, followed by the State of Justice of acting Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, 89 seats.

Could this election result be trusted?

One paradoxical argument in favour of the trustworthiness of the result published by IHEC is that the “loser”, al-Maliki, immediately started to talk about fraud and asked IHEC to undertake a total recount manually, which this independent authority wisely refused to do. After having been election observer in as different countries as Russia, Palestine, Georgia and Indonesia, my experience – and I know this is shared by most colleagues – is that only a very dominant regime is able to organize massive election fraud on a nationwide level.

The management of large-scale fraud is only possible with a considerable number of officials involved, acting because they are dependent or scared of the dominant rulers. I don’t know of any case where this has been achieved by the opposition! Thus, the reaction of al-Maliki cannot be taken seriously. At the same time, the “loss” of al-Maliki shows that he himself has not been dominant enough to be able to guarantee his own victory by manipulation. This is not surprising, because, as most observers know, there has been no dominant power on a nation-wide level in Iraq since the fall of Saddam Hussein and the end – at least legally - of the U.S. administration.

At the same time there are of course cases of regional and local dominance in Iraq, one example being Kurdistan where the two major parties, KDP of Barzani and PUK of Talabani, for electoral purposes have united into one dominant alliance. However, even in Kurdistan a challenger, Gorran (Change) managed to make a break-through and gain eight seats in the National Parliament. Also, the fact that al-Iraqiyya got seats in 12 out of 18 governorates shows that there are limits of sectarian dominance in most provinces.

Not only my own group of election observers, but also other international observers and, most importantly, Iraqi organisations with tens of thousands of observers, such as Shams and Tammuz, have directly or indirectly reported that even if breaches of rules and local cases of direct fraud have been recorded, there has not been massive fraud on a scale that could have influenced the over-all outcome. The National Iraqi Network of Observers, which fielded 4500 observers from 14 NGOs, on March 30 declared that the elections, despite minor infractions, had been “in accordance with international standards”.

One argument against taking the elections in Iraq seriously has been that they have taken place under occupation. I will not refute this by the legalistic argumentation that the occupation as a means of administration ended already when the infamous Paul Bremer was replaced by an Iraqi government or at the latest with the parliamentary elections of 2005. Let’s accept that a real occupation is still going on, even if most Iraqis rarely see any US soldiers since late 2009. Normally an occupation would disqualify any election.

But in January 2006 elections were held in occupied Palestine and the most widespread reaction of protest all over the world was not about the fact that these elections took place under Israeli occupation, but about the refusal of both the occupiers and their Western supporters (who had demanded the elections to be held) to respect the outcome, i e the victory of Hamas. I cannot see any tenable argument why progressive people and supporters of national liberation and independence should support the 2006 elections in Palestine but discard the 2010 elections of Iraq.

Of course even other Iraqi politicians than al-Maliki have claimed that fraud has occurred. However, apart from the three major alliances in Arab Iraq, Allawi’s, al-Maliki’s and that of the major Shia-organisations, including supporters of al-Hakim and Sadr, as well as the two Kurdish blocs, also two smaller secular parties got candidates elected. Thus the Iraqi parliament will have seven distinct political groups, in addition to around a dozen representatives of the religious minorities, such as Christians, Yezidis, Sabeans. There will be 82 female MPs.

Many major democratic parliaments are a lot less pluralistic without their democratic representativity being questioned – among them the U.S. Congress! Three weeks after the elections the Guardian commented: “As expressed at the polling boxes a considerable portion if the voters wish to step on the road of the Secular Nationalists”.

It is noteworthy that neither the occupation nor the risks of fraud prevented most progressive and secular political forces from participating in the Iraqi elections. One well-published incident was the banning of hundreds of candidates shortly before Election Day because of their alleged connections to the outlawed Baath party, an action that was condemned as illegal by many, including the EU observation team. However, this did not prevent the party of one of the most prominent victims of the ban, Salih al-Mutlaq, from actively participation in the election campaign (after, it is true, serious initial hesitation). Also, the Iraqi Communist party took part in the elections.

There is no doubt that the USA plans to remain strongly, if non-militarily, in Iraq. Does this mean that all those of us who opposed the invasion of 2003 and still are convinced that it was illegal and counterproductive, must disqualify the elections of March 7 and consider all Iraqis who participated in the elections as treacherous and collaborating “quislings”? Should we support the “resistance”?

I really don’t think so. As far as I know the armed “resistance” is indiscriminately killing everybody who does not surrender to a particular sect, be it al-Qaida or something else. 38 Iraqis paid with their life for choosing to take part in the elections, and many have met with the same fate since, unknown for what sin. The vast majority of Iraqis who are opponents of the U.S. invasion and continued U.S. dominance in their country chose to actively participate in the March 7 elections.

There is no reason for the international community and non-Iraqi supporters of real independence and prosperity for Iraq not to respect their choice, which also implies respecting the outcome of the elections.

Without doubt this may be exploited by the USA to try to acquire legitimacy post factum for the illegal invasion of 2003. I don’t think the international community will fall into that trap. At the same time it is obvious that to just demand “The U.S. – out of Iraq!” is a totally insufficient progressive position.

Solidarity with the people of Iraq requires much more. The time for slogans and armed “resistance” has passed, now it is time to support all those Iraqis who want to develop their country into a modern, secular welfare democracy, where women, hopefully, will play a much more influential role than before and than in most parts of the Arab world.

Per Gahrton

* Former Member of the European Parliament (1995-2004), Greens, Sweden

Editor's note

Still in late May, there is no clarity about the government to be formed on the basis of these elections - as analysed here by Aljazeera

*

Copyright

© TFF & the author 1997 till today. All rights reserved.

Tell a friend about this TFF

article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

Get

free TFF articles & updates

|