Assessing

the United Nations

after the Lebanon War 2006

|

TFF

PressInfo # 241

August 15,

2006

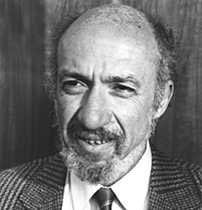

Richard

Falk

Professor

emeritus

Princeton University, TFF Associate

|

|

Of course, we all breathe a bit

easier with the news of a ceasefire in Lebanon even if

its prospects for stemming the violence altogether are

not favorable at this time. And after dithering for 34

days while the bombs dripped and the rockets flew we need

to acknowledge that the United Nations, for all of its

weaknesses, plays indispensable roles in a wide array of

international conflict situations. It is notable in this

instance that despite Israel's discomfort with UN

authority, and the reluctance of the United States to

accept any UN interference with its foreign policy

priorities, as in Iraq, both countries were forced to

turn to the UN when Israel's war against Lebanon ran up

against the unexpectedly strong Hezbollah resistance.

At the same time this is certainly

not a moment to celebrate the UN for fulfilling its

intended role as dedicated to war-prevention and the

defense of states victimized by aggression. Perhaps,

it is an occasion to take stock of what to expect from

the UN in the early part of the twenty-first century,

concluding that the Organization can be regarded neither

as a failure nor as a success, but something inbetween

that is complicated and puzzling.

The

origins and the hopes

After World War II a mood of relief

that the war was over was mingled with satisfaction (that

the German and Italian fascism and Japanese militarism

were defeated) and worry (that a future major war might

well be fought with nuclear weapons, and even if not,

that military technology was making wars more and more

devastating for civilian society). One hopeful response

was the establishment of the United Nations on the basis

of a core agreement that recourse to force by a state,

except in cases of strict self-defense was

unconditionally prohibited. This norm was supposed to be

supplemented by machinery for collective security

intended to protect victims of aggression, but this

undertaking although written into the UN Charter has

never been implemented.

The victorious countries in World

War II plus China were designated as Permanent Members of

the UN Security Council and given the right to veto any

decision. The intention here was to acknowledge that the

UN could not hope to ensure compliance with international

law by these dominant states, and to avoid raising

expectations too high it was better to acknowledge this

deference of 'law' to 'power' restricted the role of the

UN.

But what was not anticipated in

1945, and has now again damaged the reputation of the UN,

was the realization that the Organization could serve as

an instrument for geopolitics in such a way as to

override the most basic restraints on war making built

into the UN Charter, but this is exactly what happened in

the context of Israel's war on Lebanon.

"Indicative

of just how low the expectations to the UNSC have

fallen..."

The UNSC stood by in silence in the

face of Israel's decision to use the pretext of the July

12th border incitement by Hezbollah, involving only a

small number of Israeli military personnel, to launch all

out war on an essentially defenseless Lebanon. A month of

merciless Israeli air attacks on Lebanese villages and

cities has taken place, while the UN refused even to

demand an immediate and total ceasefire to the obvious

dismay of the UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan. And even

this benchmark is indicative of just how low expectations

have fallen with respect to UNSC action when there exists

any serious friction between the UN Charter and the

policy priorities of the United States as the controlling

member of the Organization.

It should be recalled that the it

was the US Government that declared the UN 'irrelevant'

in 2003 when the Security Council at least stood firm,

and refused to authorize an unlawful invasion of Iraq.

With Iraq, too, the experience, more than anything else,

underscored the fallen expectations associated with the

UNSC. It was then applauded for not mandating aggression

against Iraq, but when the invasion went ahead anyway in

March 2003, the UNSC was complicit with aggression by way

of silence, and later went even further later on, acting

as a junior partner in the American-led occupation of

Iraq.

The point being stressed is that

the UN is unable to prevent its Permanent Members from

violating the Charter, but worse, it collaborates with

such violations in support of its most powerful member.

The UN has become in these

situations, sadly, more of a geopolitical instrument than

an instrument for the enforcement of international law.

This regression betrays the vision that the guided the

architects of the UN back in 1945, chief among whom were

American diplomats.

The

Nuremberg Promise has long since been

forgotten

It should be also recalled that

when German and Japanese surviving leaders were

criminally punished after World War II for waging

aggressive war at the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials the

prosecutors promised that the principles of law applied

to judge the defendants associated with the defeated

countries would in the future we applicable to assess the

behavior of the victorious power then sitting in

judgment. This Nuremberg Promise has been long since

forgotten by governments, but it should not be ignored by

public opinion and citizens of conscience

everywhere.

Resolurion

1701 undermines the UN's own authority

Nothing illustrates this fallen

condition of the UN better than the one-sided UNSC Res.

1701 ceasefire resolution finally approved by unanimous

vote on Aug. 11th. This resolution, although in some

respects a compromise that reflects the inconclusive

battlefield outcome, is tilted in many of its particulars

to favor the country that both wrongfully escalated the

border incident and carried out massive combat operations

against civilian targets in flagrant violation of the law

of war: Res. 1701 blames Hezbollah for starting the

conflict; it refrains from making any critical comment on

Israeli bombing and artillery campaign directed at the

entire country of Lebanon; it imposes an obligation to

disarm Hezbollah without placing any restrictions on

Israeli military capabilities or policies; it places

peacekeeping forces only on Lebanese territory, and is

vague about requiring the withdrawal of Israeli armed

forces; it still fails to censure Israel for expanding

the scope of its ground presence in Lebanon by 300% to

beat the ceasefire deadline, and it calls for the

prohibition of 'all' attacks by Hezbollah while requiring

Israel only to stop 'offensive military operations,'

leaving the definition of what is offensive in the hands

of policymakers in Tel Aviv and Washington.

We learn some important things

about the United Nations from this experience. First, it

is incapable of protecting any state, whatever the

circumstances, that is the victim of an aggressive war

initiated by the United States or its close allies.

This incapacity extends even to proposing resolutions of

censure.

Secondly, the UNSC, while not

actually supporting such claims of aggressive war, will

collaborate with the aggressor in the post-conflict

situation to ratify the effects of the aggression. This

combination means effectively that the Charter

prohibition directed at non-defensive wars applies only

to enemies of the United States. Any legal order that

achieves respect treats equals equally. The UN is

guilty of treating equals unequally, and thus constantly

undermines its own authority.

'Punitive

self-defence'? Israel's illegitimate use of retaliating

force

There is another disturbing element

that concerns the manner in which states aligned with the

United States are using force against non-state actors.

Such states, of which Israel is a leading example, engage

in what a law commentator, Ali Khan, has called 'punitive

self-defense.' UN Charter Article 51 deliberately tried

to restrict this option to claim self-defense by

requiring 'a prior armed attack,' which was definitely

understood, as being of a much more sustained and severe

initiation of violent conflict than an incident of

violence due to an isolated attack or a border skirmish.

More concretely, the events on the borders of Gaza and

Lebanon that gave rise to sustained Israeli war making

did not give Israel the legal right to act in

self-defense, although it did authorize Israel to defend

itself by retaliating in a proportionate manner. This

distinction is crucial to the Charter conception of

legitimate uses of international force.

What punitive self-defense means is

a deliberate policy of over-reaction such that there is

created a gross disproportion between the violence

inflicted by the non-state actor, in the Lebanese

instance, Hezbollah, and the response of the state actor

Israel.

It also means, contrary to the

UN Charter and international law, that every violent

provocation by a non-state actor can be treated as an

occasion for claiming a right to wage a full war based on

'self-defense.'

This punitive approach to

non-state adversaries completely negates a cardinal

principle of both international law and the just war

tradition by validating disproportionate uses of

retaliatory force.

We

must not become cynical about the role of the

UN

This discouraging interpretation of

what to expect from the United Nations in war/peace

situations should not lead to a cynical dismissal of the

Organization. We need the UN to step in, as in Lebanon,

when the arbiters of geopolitics give the signal, and

help with the post-conflict process of recovery and

reconstruction.

But we should be under no

illusions that this role adequately carries out the

vision of the UN contained in its own Charter or upholds

the most basic norms of international law.

How

can this situation be improved?

There are three areas of effort

that are worthy of attention:

•

Perhaps, most important, is the recognition by major

states that war is almost always a dysfunctional means of

pursuing their security interests, especially with

respected to addressing challenges posed by non-state

actors.

In this regard, odd as it may seem,

adherence to the limits imposed by international law may

serve national interests better than relying on military

superiority to override the restrictions on force

associated with the UN Charter; note that the United

States would have avoided the worst foreign policy

disasters in its history if it had not ignored these

restrictions in the Vietnam War and the Iraq War; in

their essence, limiting war to true instances of

self-defense is a practical restriction on state

sovereignty agreed upon by experienced political

leaders;

•

Of secondary importance is

for the members of the United Nations to take more

seriously their own obligations to uphold the Charter; it

may be appropriate in this spirit to revive attention to

the so-called Uniting for Peace Resolution 337A that

confers a residual responsibility on the General Assembly

to act when the Security Council fails to do

so.

This 1950 resolution was drafted in

the setting of the Cold War, with an intention to

circumvent a Soviet veto, but its use was suspended by

the West in the wake of decolonization, which was

perceived as making the General Assembly less supportive

of Western interests than had been the case in the early

years of the UN.

In present circumstances, the

General Assembly could be reempowered to supplement the

efforts of the Security Council where an urgent crisis

involving peace and security is not being addressed in a

manner consistent with the UN Charter; along similar

lines, would be an increased reliance on seeking legal

guidance from the International Court of Justice when

issues of the sort raised by the Israeli escalation

occurred. [Please see TFF's

Open Letter to the President of the General

Assembly concerning the

Uniting for Peace resolution that the author has

supported].

•

And finally, given these

disappointments associated with the preeminence of

geopolitics within the UN, it is important for

individuals and citizen organizations to act with

vigilance.

The World Tribunal on Iraq, taking

place in Istanbul in June 2005, passed 'legal' judgment

on the Iraq War and those responsible for its initiation

and conduct. It made the sort of legal case that the UN

was unable to make because of geopolitical

considerations. It provided a comprehensive examination

of the policies and their effects, and issues a judgment

with recommendations drafted by a jury of conscience

presided over by the renowned Indian writer and activist,

Arundhati Roy.

Such pronouncements by

representatives of civil society cannot obviously stop

the Iraq War, but they do have two positive effects:

first, they provide media and public with a comprehensive

analysis of the relevance of international law and the UN

Charter to a controversial ongoing war; secondly, by

doing so, they highlight the shortcomings of official

institutions, including the United Nations in protecting

the wellbeing of the peoples of the world.

Get

free articles & updates

Få

gratis artikler og info fra TFF

© TFF and the author 2006

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

You are welcome to

reprint, copy, archive, quote or re-post this item, but

please retain the source.

Would

you - or a friend - like to receive TFF PressInfo by

email?

|