|

Following

Gandhi's Path 2

Settling

Conflicts in Dharamsala

By Jan

Oberg,

TFF director

The bus leaves Delhi at around 5 o'clock P.M. (maybe).

There are two kinds of passengers: Tibetan monks and

occidental backpackers. The road north from Delhi appears

to be full of completely chaotic traffic. The trip is

said to provide wonderful sights of the mighty Himalayan

Mountains. However, when we arrive it is pitch-black and

we had spent a long time dozing leaning on one another's

shoulders. When I sometimes awake, I can't see much more

than rock-faces running away either to the right or the

left in erratic beams of light. One thing is sure, Indian

bus drivers really do know how to manage on serpentine

roads…

After thirteen hours of bus riding, I arrive at

Dharamsala, which is a religious, political and cultural

centre for a couple of hundred thousand exiled Tibetans

and lies at a height of 1300 metres in the Himalayas. In

the chilly darkness I wrap myself in a special

khadi-blanket I bought in Delhi's Gandhi Museum with

thoughts of the cold in the mountains. I start walking on

a narrow mountain way with no street-lights at all but

with locked-up hovels alongside. Suddenly an unobserved

shawl-clad figure emerges from the obscurity and asks

where I'm going to. "To Kashmere House", I reply and five

minutes later a mini cab is driving me to the place. This

is where I and my friends from Danish Centre for Conflict

Resolution shall teach young, exiled Tibetans how to

analyse and handle situations of conflict and how the

big, outside world - which they have good reasons to feel

deserted by - actually works.

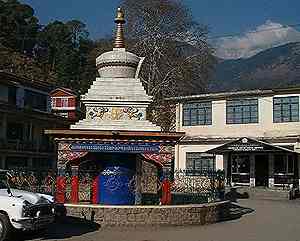

Photo Jan Oberg, © TFF

2001

Bus Square in

Dharamsala

Dharamsala is divided in topographical levels.

Dharamsala proper, with the hospital, the municipal

administration and the Tibetan cultural centre (Nobulinka

Institute) is situated in the beautiful and impressive

Kanga valley, above which there are always huge dark

birds of prey circulating. That is some 10 kilometres

from Lower Dharamsala, through rice fields and wonderful

nature. Lower Dharmsala, where I had arrived, consists

mainly of dwelling houses, bazaar-crowded streets and two

Internet cafés.

I knock on the windows and doors to Kashmere House, a

fairy-tale-like building of colonial origin, and finally

a night watchman appears. I get a couple hours of normal

sleep. Then it is time to explore a bit. On the narrow

bumpy road it is about 5 kilometres uphill to Gangchen

Kyishong, the government block housing the Tibetan

Parliament, various departments and the security office.

However, I choose to walk and climb for about half an

hour along one of the many slippery shortcuts, sometimes

wandering all alone, sometimes encountering small groups

of cottages and poultry-farms, and sometimes meeting

shepherds, old women, cows and goats. It takes another

hour of walking to reach a height of 1768 metres and to

find Upper Dharamsala, or McLeod Ganj - the local

tourists' Mecca with restaurants, temples, shops,

handicrafts, museums, post offices, book-sellers and His

Holiness the Dalai Lama's amazingly plain and

architecturally dull temple, Tsuglagkang.

Photo Jan Oberg, © TFF

2001

Government Square

with the parliament in the background

David McLeod was a "lieutenant governor" in the 1850s

when the town was a British barracks. The small colonial

shop looks as if McLeod will step through the door at any

minute. In those days Dharamsala was inhabited by the

half nomadic Gaddi people who were neither "Indians" nor

Tibetans.

I am very proud of having been invited to assist these

eager-to -learn and humorous young Tibetans. But why do

they want to establish their first-ever Tibetan centre

for handling conflicts? The answer might be found in the

topic of a lecture I have been asked to give at the

exile-government's Ministry of Foreign Affairs: how to

settle conflicts when the counterpart is mightier and

shows no interest in carrying on a dialogue.

Because this is what is troubling the Tibetans in a

nutshell: 5-6 million people were occupied - as they see

it - by a superior force. 6-8 million Chinese people have

since moved to Tibet, where the Tibetans are themselves

now a minority in their own historically independent

country. Furthermore, the Chinese have based the larger

part of their nuclear weapon program in Tibet, thus

polluting the globally unique fauna and flora - depleting

them or so they outright disappear.

Having said that much I think I should also emphasise

that I haven't been either in Tibet or visited Beijing in

order to study and comprehend the entire matter of Tibet.

I actually would love to do that. Books on Tibet and the

Internet have taught me that sound arguments can be found

on all sides.

Another reason why Tibetans in India wish to learn how

to settle conflicts is that there is a conflict between

the Tibetans born in India, who look upon themselves as

better educated and more "civilised", and those born on

the other side of the mountains in Tibet, who the former

consider to be more "primitive". Conflicts even exist

between the group of young people who appreciate the

Dalai Lama and non-violence, and the more revolutionary

group that believes that - at least after him - there

must be an armed revolution since non-violence has not

achieved anything. Moreover, there are also conflicts

between Tibetans and Indians within the local

societies.

Instead of traditional instructing or lecturing, we

had a dialogue that was to the benefit of both parties.

It's hard to imagine anything more meaningful than

cooperating with these 20 to 30-year-old people. They and

their families have gone through a lot of hardship, are

all refugees, deeply religious and yet they have kept

their tolerance, their curiosity and their dignity

intact. In their company I felt very happy about being a

peace researcher and activist. We parted as the best of

friends.

It strikes me that, as things are now, they don't have

much of a chance to see a free Tibet during their

lifetimes. If there will be an independent Tibet, it must

be shared between the Tibetans and all the Chinese

residents, who themselves are victims of a big power

game. Not an ethnically cleansed Tibet. I never saw any

hate in the eyes of these youths, nor heard them say

anything malevolent.

Photo Jan Oberg, © TFF

2001

Monk in Dharamsala

Tibetans are generally very positive and deeply

religious. They believe both in respect and, just like

the Dalai Lama, in laughter! Buddhism is all about how to

overcome suffering, attain happiness, tolerance and

empathy, as well as about striving for "mindfulness" and

"loving kindness" - to live wholly attentive and with the

friendliness of love. That's not a bad start for a

conflict settlement and reconciliation philosophy!

If I succeeded in giving them anything at all in

exchange for what they taught me about the Tibetan

conflict, then it was widening their views on Gandhi and

non-violence as an active, not passive, philosophy and

policy. There are many similarities between the Lama and

the Mahatma, but the latter was even a political and

strategic fighter.

Translated by Alice

Moncada

Translation edited by Sara E. Ellis

Other

articles about India, "Following Gandhi's Path" and

picture galleries

©

TFF 2002

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

|