|

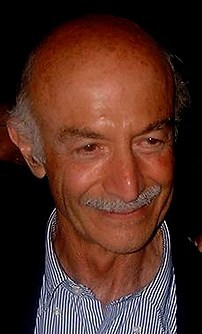

Thinking

Across Cultures

with

Nur Yalman

By

Patti

M. Marxsen of the

Boston

Research Center for the 21st Century

and

Nur

Yalman,

Professor of Social Anthropology and

of Middle Eastern Studies,

Harvard University

TFF

associate

October 19, 2002

Nur Yalman is Professor of Social Anthropology and of

Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. He has

published numerous books and articles, from his first

entitled Under the Bo Tree: Studies of Caste, Kinship,

and Marriage in the Interior of Ceylon (University of

California Press, 1967) to recent essays on the role of

science in international conflicts and the relationship

between terror and cultural diversity. Since September

11, 2001, Professor Yalman has been a compassionate

critic of the U.S. military response to global terrorism.

In the Fall of 2001, his course entitled Thought and

Change in the Contemporary Middle East was overwhelmingly

popular among students. Patti Marxsen, BRC publications

manager, spoke with Professor Yalman as the first

anniversary of September 11th approached.

------------------

PM: I'd like to start by just asking you about your

own journey. Could share with us some of the experiences

and motivations that brought you to your interest in

cultures, religions, identity, and the condition of

humanity?

NY: I was brought up in Istanbul, Turkey, which is a

very cosmopolitan and very complicated place in the

middle of many cultures and continents: Europe, Asia,

Africa. I had a German governess and before that I had an

Austrian governess, both of whom taught me German. My

mother and father also spoke French. And at school I had

English. That combination, with Turkish of course, opened

up to an interest in other cultures and how they relate

to each other. I think the experience of really being

involved in other languages early on opens you up to an

interest in other cultures.

PM: When did you first get a chance to do the field

work of anthropology?

Cambridge University gave me a good background and,

later, I worked on my Ph.D. in Sri Lanka. I spent

numerous years in Sri Lanka in very out of the way

places. And that was wonderful because it really opened

my eyes to the riches of Asian cultures and

civilizations. I went back to Cambridge where I was

elected as a fellow of one of their old colleges,

Peterhouse. Then I went back to Turkey and, meanwhile, I

had an invitation from a research center in California. I

was still very young and the idea of California was…

paradise.

PM: Has this study of anthropology turned out to be

what you thought it would when you were first embarking

your career?

NY: I had not realized how very exciting it was going

to turn out to be. It has indeed turned out to be the

most interesting and the most fascinating study, because

you really deal with the immense variety of human

experience and human behavior, human thoughts, and human

imagination. I really can't think of many other fields

which really open you up in the same way.

PM: Your field, social anthropology, is all about how

humans interact with one another, how we structure our

societies, and work out our differences. As Americans

reflect on our post-9/11 stance in the world&emdash;

which has been militaristic and often mistrustful of

foreign cultures&emdash;I'd like to know if it's valid to

suggest that the policies in democratic states typically

mirror the values of the culture?

NY: Yes and no. The degree to which the best American

values are expressed in the American government would be

a controversial question because democracies have very

positive aspects&emdash; the openness, the desire for

equality, the hospitality, the openness to

immigrants&emdash; but they also have some negative

aspects. That is to say they lend themselves to mass

manipulation. Also, there is a violent edge to American

society and, regrettably, some of the American reactions

to terrorism have tended to go in an extremely violent

direction.

PM: What is the source of this tendency toward

violence?

NY: The metaphor of 'control' is an aspect of American

society. We see this when it comes to controlling crime,

especially in black neighborhoods which are vigorously

policed and controlled. There are other ways of handling

social problems. We could give much more attention to

education, to improving the lives of the poor, to

improving the lives of the racially disadvantaged people

in a much more serious way.

PM: How does this controlling instinct play out in the

international arena?

NY: The metaphor of controlling other people through

police action is something that the U.S. has been willing

to do in many parts of the world. And it is a method that

doesn't work terribly well when you don't understand what

is going on in these other places. That's my criticism of

the kind of violent reaction we have had to either the

Taliban regime or to the Palestinian matter.

PM: What could we have done differently in response to

the Taliban regime?

NY: I would have preferred to have much more

international involvement, particularly involving the

Islamic societies, to put pressure on this nasty regime.

We could have used the more liberal Islamic

countries&emdash;all of which indicated that they were

very unhappy with what was going on&emdash;to put

pressure on these people. I think we would have had a

much less violent result and I think we might have

achieved the same thing in the end. We might even have

achieved a somewhat more stable Afghanistan. At the

moment, Afghanistan looks very unstable and the

instability has affected Pakistan, Kashmir and India, all

of which are nuclear powers.

PM: It sounds like you're saying that our 'violent

edge' draws other peoples and regions into our way of

resolving conflicts. Is this how the 'metaphor of

control' operates?

NY: Yes. The violent reaction has had widening effects

both in the region of India and Pakistan, which is very

dangerous, and also in the Israel-Palestine affair. Since

September 11th, we have witnessed the Israelis using the

same excuse as the United States to declare "war on

terrorism."

PM: Has this period since 9/11 taught Americans

anything about how we operate as a society?

NY: There is the blind following of the desire to get

revenge, to get even with these nasty fellows. At the

same time, I think we're beginning to see slowly quite a

lot of thoughtful material coming out in some

publications, such as the New York Review of Books, the

New York Times, and the Washington Post.

PM: What do you think accounts for that shift toward a

more thoughtful approach?

NY: This has been a very profound trauma for America.

In a real sense, this cocoon in which we were living in

here in America, this beautiful sense of security, this

isolation from the rest of the world&emdash;isolation by

two great oceans and by a very friendly north and a

somewhat less friendly south&emdash;has allowed Americans

to feel that they are in a charmed continent. It's not

too surprising that it has taken time for Americans to

assimilate the threat of terrorism. I don't think other

societies have had that kind of shock out of a period in

which they felt as secure.

PM: Were you as shocked as the rest of us?

NY: For those of us who had been watching the terrible

things that were taking place in the Middle East, it came

as no surprise whatsoever. I was growing fearful of where

we might be heading with the kind of tensions that were

rising in the Middle East. I thought the most desperate

reactions might be expected, even nuclear reactions could

be expected.

PM: So it could have been worse?

NY: It could have been much worse. And it is possible

that it might be worse yet, unless the root cause of this

is settled.

PM: What is the root cause?

NY: I do think the root of the problem has to do with

racism. And the root of racism has to do with the way so

many countries, including the United States, have

regarded Muslims and Arabs in the past. That is to say,

they have always considered these people to be

second-rate persons. From World War I onwards, once

Britain and France took over the Arab countries and

dominated them, they did not really consider their

interests. When you look at the historical background, it

is quite clear that Jews and Muslims existed for

centuries in great peace together all over the Middle

East. The Jews have contributed immensely to the

civilization of Islam: they contributed to music, to the

arts, to literature. Everything gets turned around after

World War II, for it is then that the European problem of

racism&emdash;racism against the Jews,

anti-Semitism&emdash;is transferred to the Middle

East.

PM: How do we reconcile the rich history of Islamic

culture with the violent acts that have now become

associated with Islamic societies?

NY: The kind of terror and militancy we are seeing in

Islam today has to do with something very particular, a

particular problem in the Middle East that has been

festering for almost all of the last century&emdash;that

is to say the problem of Palestine.

PM: Knowing and understanding all the pieces of the

situation as well as you do, if you could have given

Ariel Sharon advice earlier this year, what would you

have said to him?

NY: I would have said make peace, not war. I would

have said give up those settlements and make an

arrangement with these people.

PM: A two-state solution?

NY: A two-state solution.

PM: Why not Edward Said's recommendation of a

one-state solution?

NY: I think we must maintain hope that we can have

complex states, rather like the direction in which the

European Union is going, in which human rights are

respected.. This can happen when very different people

from divergent cultures come together around certain high

ideals, as in the United States where we have the high

ideals of the Constitution.

PM: But isn't that the idea behind a one-state

solution? Is it possible that the Israelis and the

Palestinians might live under a Constitution that extends

rights to Jews and Muslims?

NY: It's not possible for the time being because their

cultures, as yet, are too different. Most of the Israelis

are very much attuned to a kind of European culture. Most

of the Palestinians are not. It will take time for them

to come to terms with each other.

PM: Do you believe these two societies will be able to

find common ground?

Right now, of course, all bets are off. Everything is

so shaken up that one wonders what sort of society can

exist there. But the future for the Israelis must involve

coming to terms with the fact that they live in a Middle

Eastern environment and they will have to make friends

with the people around them. They can't keep relating to

their neighbors as enemies, because that will make them

very uncomfortable for the future. They must make some

adjustments, and maybe even some sacrifices. The most

important sacrifice they must make, in my opinion, is

that they should get out of those settlements, which they

have no right to anyway.

PM: What can the United States do to help get us to an

era of peace and stability in this region?

NY: The United States is in a very difficult position

because there is a very powerful internal dynamic which

does not recognize the significance and importance of the

Palestinian cause and is very much geared to supporting

the most extreme kinds of Israeli actions.

PM: It's troubling for many Americans to be in a

position of endorsing this kind of disconnect, this

racism, with our Middle East policy. Do you imagine that

our policies might change?

NY: It looks very difficult for the policies to change

and this is the reason why the matter appears to terribly

intractable. The United States that is the only power

with the keys to a solution, and yet the keys are in the

pocket of the President and he will not, or is not able,

to bring them out.

PM: Couldn't the Islamic countries still get together,

as you have suggested elsewhere, and craft a solution to

the Israli-Palestinian conflict or act independently to

bring Osama bin Laden to justice?

NY: Of course they could. But because the United

States has taken the initiative and is, in fact, involved

in very elaborate military action, there is really no

space there for the Islamic countries to get in on in

this activity. It would have to be organized with the

United States.

PM: America has supported the Israeli government to

such a huge extent that we are clearly in the thick of

it. But why do Islamic leaders still need our keys, so to

speak, to unlock a solution to the bin Laden matter in

particular and to the threat of global terrorism in

general?

NY: As long as the United States supports Israel so

strongly, a position which makes life impossible for the

Palestinians, it is very difficult for the Palestinians

and their circle of supporters&emdash;first of all the

Arab states&emdash;to take a position in which they

criticize those who are supporting their cause. Bin Laden

is, effectively, supporting the cause of the

Palestinians, the Arabs, against the colonial powers.

This becomes a very compelling argument.

PM: So you're saying that the Palestinian cause

remains central to all of the Arab states.

NY: That has not changed and it is not going to

change. And worse, I think the Palestinian cause is

bringing about something that is totally unexpected which

is a kind of national consciousness among Arabs. The

Arabs have been, so far, totally divided; they have been

totally diverse in their governments, attitudes,

relations with the West, and with each other. But this

cause is bringing the people together. In time, we are

going to see much more of a national consciousness emerge

among the Arabs, which is going to be much more difficult

to handle all around, for Israel especially, but also for

the United States.

PM: Do you see a contradiction in America's

declaration of war on terrorism and our support for what

the Palestinians experience as terrorism on a day-to-day

basis?

NY: That is exactly what the Palestinians think. But

of course, it is ironic that the Israelis think the same

thing in a parallel way and regard Palestinians as

terrorists.

PM: So what is terrorism? If we're all terrorists,

what does it mean?

NY: The United Nations spent a lot of time trying to

figure out what terrorism is and they didn't reach any

conclusion. Then there was a meeting of the Islamic

countries and they tried to come to an agreement, and

they didn't come up with anything. It cannot be easily

defined.

PM: I read an article recently not long ago by a

Women's Studies professor, Catherine McKinnon, who was

proposing that domestic violence be understood as a form

of terrorism.

NY: I would entirely agree with that. Domestic terror

is the worst kind of terror because it's very intimate

terror. One of the things one sees as an anthropologist

is the terrible treatment of women in culture after

culture after culture. That really must change through

education.

PM: You've said elsewhere that we need to be better

governed on 'spaceship Earth.' What would better

governments look like? Could you make a few

suggestions?

NY: Well, I am very much in the mind of the principles

of the French Revolution.

PM: Let's not forget, they were terrorists too.

NY: Well, yes, Robespierre said that terror was a form

of virtue, to his eternal misfortune. But a good society,

a well-governed society, is one in which people feel they

have equal chances to find fulfillment and where there is

a sense of justice. How do we achieve that in the world?

I believe that this idea of human rights&emdash;the

rights of individuals &emdash;must be respected

throughout the world. And I must add that this is a

highly idealistic, highly impractical position.

PM: How might your idealism become reality?

NY: The way to begin is by supporting institutions

like the International Criminal Court. We also need to

think about human rights in regional terms, because there

are sufficient cultural differences between regions and

their concepts of human beings and their concepts of what

is proper and what is acceptable and so on. We need to

encourage the United Nations to begin to develop regional

courts of human rights.

PM: How would this work?

NY: For instance, the European Union has now a Court

of Human Rights. Citizens of different countries can

appeal to it. It passes judgements and it exacts

punishments which are payments from governments involved.

I know this because Turkish citizens have been applying

to the European Court of Human Rights and they have been

getting justice. They are getting the Turkish government

to pay them for the miseries that have been visited upon

them.

Step by step, we'll get to a larger concept of a

supreme court of human rights within the context of the

United Nations. I think it would be extremely short sited

of the U.S. to think that its tremendous military power

is good enough, that we don't need the international

institutions. Now we need the international institutions

more than ever.

PM: And yet, we, along with Somalia, are the only two

nations who have refused sign on to the ICC. It's an

embarrassment.

NY: I agree. It has been an embarrassment for my

colleagues at Harvard Law School here. They have all been

throwing up their arms. And as I travel throughout the

world, I am asked about this. People are absolutely

stunned.

PM: If you could gather 100 leaders in a room together

and initiate a dialogue, what would you ask them to talk

about?

NY: Human rights, the rights of each individual human

being. Andre Gide said once that the individual was the

most irreplaceable of beings. A moment's thought

indicates how true this is. Individuals are

irreplaceable. Therefore, their rights are absolutely

vital and extremely precious.

PM: Can one envision peace without human rights being

honored?

NY: No.

PM: So we have to start there…

NY: I think so, yes. And I think the United States is

in a particularly good position in this respect because

notwithstanding all that we have heard about how much

people hate us, in fact the U.S. with its wonderful

Constitution, with its wonderful record of welcoming

people to this country and giving them the opportunity to

flourish in this country, has been a beacon of liberty

and hope for peace for the rest of the world. It pains me

to see that that immense source of good will is being

lost.

©

TFF & the author 2002

Tell a friend about this article

Send to:

From:

Message and your name

|